Verbal Map studio visit artist Jennifer Vanderpool

As in-the-flesh studio visits are a tad hampered at the moment, I reached out to artist Jennifer Vanderpool for a virtual visit.

Jennifer is a multi-disciplinary artist and community arts activist. Her social art practice investigates post-industrial communities, the impact of deindustrialization, and workers’ lives beyond geopolitical boundaries. She’s exhibited internationally in gallery and museum shows, and her curatorial projects have received critical acclaim. Currently, she is a US-UK Fulbright Artist Fellow.

I have known Jennifer for twenty-plus years, and we have collaborated on several projects. I am always in awe of her intelligence, artistic depth and sophistication, resourcefulness and tenacity. She’s one of the art world’s bright spots. To read more about Ms. Vanderpool, click here.

What would you say you want your role to be as an artist? What would you like your work to do in the world? And has that changed over the years?

I would describe myself as a storyteller. I develop narratives in my exhibitions through the interplay of materials and mediums. Thematically, my earlier work focused on gender roles. I fabricated ideas of the social construction of gender through consumer goods and consumption in the form of overwrought crafted sculptural and video installations.

The decorative qualities of these installations are still present in my archival photographic interventions. I begin my current projects in museum and institutional archives researching photojournalist imagery, advertisements, and other ephemera, magazines, films, and material culture.

I interpolate my photographs and design elements with these historical visual culture images to create photographic intervention digital prints, integrate archival footage into my documentary films, and present selected material culture from diverse institutions to develop community-specific and site-responsive exhibitions.

The theme of my current work encompasses the traumas of disenfranchised peoples and communities to highlight cultural amnesia that perpetuates the status quo. Through my multi-faceted approach, I hope to create a platform for storytelling as a mode of public discourse that underscores structural inequalities and contributes to calls for social reform.

Looking at the span of your art production, your work seems to explore the coupling of polarized premises – idealization and disillusionment; equity and inequity; found and invented; natural and artificial. There’s also always a nod to feminism.

Your older, larger-scale installations were, as perfectly described by an art writer, “baroque.” Comprised of an eclectic glut of detritus and discarded materials constructed into vibrant, candy-colored and slightly menacing arrangements that mimic natural forms, the work was concentrated yet maintained a playful, push-pull charm.

Over the past ten years or so, you’ve made a dramatic shift in your practice. While once vivacious and extroverted, the work is more quietly cerebral. Your installations have a more documentarian feeling with sentiments of empathy, reverence and nostalgia. Themes are expressed by a more subtle selection of imagery yet are still very intensive given the gravitas of your subject matter.

Can you elaborate on this transition? Do you think you’ll return to 3-D work?

The Hysterical Paradise exhibition at Bandini Art in Culver City in 2008 was my thesis show and included around a thousand handcrafted sculptures and seven animations. It took me a couple of years to make the installation. I was exhausted when the show closed, and I was done, just done making this kind of work. I couldn’t stand to be in my studio with the mass amounts of textiles, plastic, ribbon, and so on. I knew this phase of my art career was ending. It took a few years.

The 2009 Blomster exhibition in Sweden was in dialogue with Hystercal Paradise, as was Sagoberättelser, but the latter show was my first intervention in a museum archive. I selected minimalist textiles and drawings by the late Swedish designer Peter Condu, who died in 1986 from AIDS and whose work was largely forgotten, from the holdings. I juxtaposed his work with my ultra-baroque installation.

By 2011, I had just finished graduate school. I created Wanton for Galería Sextante in Bogotá, which included suspended gooey globe sculptures, an animation, and a series of photographs overlaid with screen prints. This exhibition was the last big project that I’ve done with sculptural works, and from that point on, I’ve been working a lot with museum archives and photography in the expanded field. At the moment, I can’t imagine crafting work for installations, but who knows.

I began fully integrating archival photographic interventions in my practice with the 2012 exhibition Hometown Story: Youngstown Steel Kitchens at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. This exhibition became my first exploration of Rust Belt communities. I constructed a prosthetic memory by integrating my narrative growing up in the Mahoning Valley after the mills closed, with an attempt to understand the social history of the region, events of deindustrialization, and these legacies in the Industrial Midwest.

At the opening, I spoke with community members. They told me about working for the corporation and how their lives and the city changed when it closed in 1973. These conversations caused me to reflect on how to frame the questions that I hoped my work would address. Listening to their anecdotes eventually led me to incorporate on-camera interviews with community members in my exhibitions.

My first effort to create a documentary began at home in Youngstown, where I started spending more time investigating post prosperity Rust Belt cities. I interviewed my grandparents about their experiences as Ukrainian immigrants who first lived in Appalachia, where my grandfather worked in the coal mines before moving to the Warren area in 1967 to work in the GM Packard Electric plant. I excerpted these conversations for the video.

I excavated details from my grandmother’s family photos, Ukrainian material culture, and Soviet clothing and lifestyle advertisements to create photographic interventions and digital prints. I included some of these compositions in the video and made a related series showcased in the gallery. Family Stories/Сімейні Оповідання opened in 2013. ArtPlatz and the Kroshytski Art Museum, Sevastopol, Crimea, Ukraine, co-organized the exhibition.

I’ve gone further afield with more recent projects. I interviewed floriculture workers for Flores Para El Trueque, 2013-17, a transnational project investigating flower farmers’ lives in Central California, Colombia, and Ecuador.

A couple of years ago, I began including art outreach efforts as facets in my exhibition. I’d always been organizing art outreach projects, but they were separate from my shows. The 2018 invitation to exhibit at Heritage Space, Hà Nội, Việt Nam, brought me back to my grandmother’s reminiscences about working as a cook in a sweatshop in the Allegheny Mountains and my mother’s stories about sewing shirt collars to pay her college tuition.

For the past several years, I have divided my time between Southern California and Northeast Ohio as I finished work for my next Rust Belt project, Untold Stories. Being home allowed me to talk with my mom about her sweatshop job transporting clothing items from seamstress to seamstress in the progressive bundle system. My conversations with my mom about her experiences working in the garment industry made me realize the importance of creating safe spaces for workers to share stories.

For Garment Girl in Hà Nội, fashion designer Phạm Hồng and I organized a craftivism project titled Remake. We fashioned a ‘factory’ in the Heritage Space gallery mimicking Vietnamese sweatshops that contractors often locate in residential homes. Then we employed social media to invite Hà Nội garment and apparel industry workers to collaborate with us. As we created new clothes from recycled ones, we discussed working conditions and how this impacted their lives and personal strategies for change.

Curator Rachel Schmid exhibited Garment Girl at the Kwan Fong Gallery of Art and Culture at California Lutheran University in 2019. The outreach component for this venue included a community swap, after which we donated the remaining clothes to a non-profit that assists teenagers in foster care.

I no longer feel that sculptural video installations are the best mediums to tell the stories of my current practice. The beauty of the pop culture materials and imagery of my earlier exhibitions has become more refined and elegant to highlight that sense of nostalgia and as well as the urgency of subject matter that I hope my current work provokes.

Vibrant patterns and patterning are a large part of your practice. In your newer pieces, patterns seem to function both as design elements and subject matter. Can you speak to the works’ relationship to pattern? How do you source your patterns? I know how much research goes into your work!

My interest in textiles and patterns comes from Ukrainian and Russian material culture from my childhood.

I first included patterns in my archival photographic interventions for Hometown Stories. When I discovered Mullins Manufacturing, which designed and fabricated Youngstown Steel Kitchens, the portrayal of women in company advertisements fascinated me. These images reminded me of the stories my grandmother told about her youth during the fifties. I pictured women wearing swing dresses topped with twin set cardigan sweaters and these feminine ladies’ ongoing struggle for gender equality.

So, the patterns in those compositions were inspired by photographs that I saw of her—somehow, my gram managed to have beautiful clothes despite not having means. I think she made a lot of her clothes, using her skills from working in a sweatshop. Some of the other patterns came from my collection of vintage clothing from the same time.

Many of the patterns in the recent projects develop from my archival research. I often select elements from such and create my own permutations to compose patterns that act as framing devices. My patterns function in multiple ways, by highlighting vignettes of workers, underscoring nostalgia when these communities were thriving, and adding a sense of levity to a serious story.

It’s both admirable and dizzying how many irons you’ll have in the fire at once – multiple shows being mounted both nationally and internationally, and numerous projects and collaborations in progress or being pitched.

Has the pandemic slowed you down? How have you had to adjust in terms of production and exhibiting your work?

Of course, I’ve had to adapt my practice to the pandemic’s horrific circumstances, but I’m incredibly grateful that I could move my studio home and be working on projects. It’s a little uncomfortable talking about this, given how so many are hurting right now. And museums and other arts organizations have suffered significant economic hardships.

This is not a small thing—the quality-of-life matters. The arts can play substantial roles in communities, not just as cultural venues or for entertainment but as platforms for storytelling that challenge hegemonic narratives and social mores and, as I suggested before, promote civil contestation. Imagining how cultural institutions first economically survive and the cultural and social roles they will play on the other side of the pandemic is a current topic of many panel discussions. Hopefully, some useful strategies emerge that can soon be implemented boots-on-the-ground.

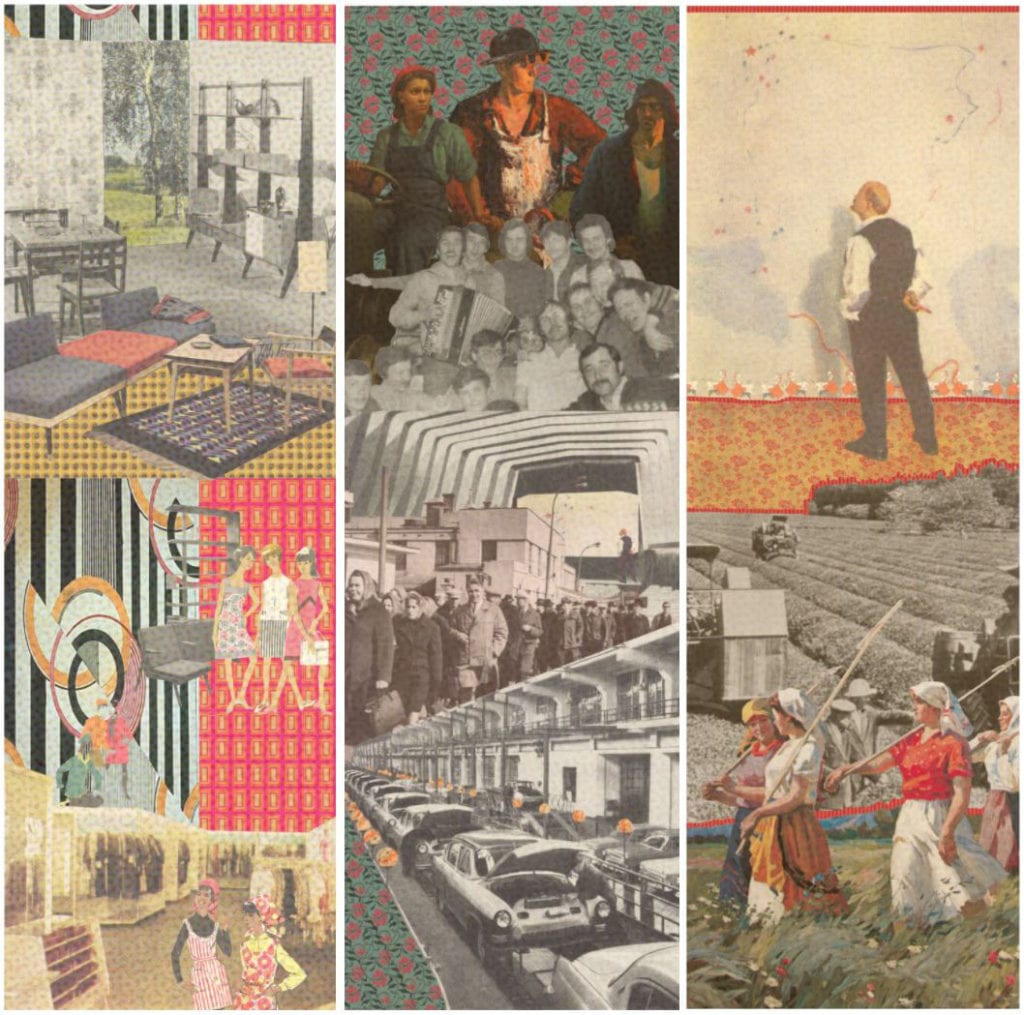

I am grateful to be partnering with various venues to being my current exhibitions online. I currently have work in the Transformations: Living Room -> Flea Market -> Museum -> Art at the Wende Museum and Archive of the Cold War. The staff actually installed the galleries and created a really great virtual walkthrough of the exhibition, which approximates being in the museum. For the show, I made a triptych titled Comrades Nikifor and Ksenia in memory of my Ukrainian grandparents, who died fairly recently and obviously had a major impact on me. This composition portrays an imaginary realism of reality and fanciful family lore about their life. I fabricated the images by abstracting and repurposing imagery from the Wende collection of Socialist Realism paintings, complementing this with details from my personal archive of family and cold war ephemera.

I’m continuing to work on Untold Stories, which crafts a social history of each deindustrialized Midwest city where the exhibit occurs. As a US-UK Fulbright Artist Fellow at the University of Liverpool, I am currently investigating relationships between these cities and those in the Industrial North of England through a photographic and video narrative project that includes stories told by noted American and British authors, scholars, and activists. Zoom has become a creative tool! I’m working with Vid Simoniti, who directs the graduate program in Art, Aesthetics, and Cultural Institutions at the University of Liverpool on this phase of Untold Stories. I’ll spend several months next year in the UK working on the project.

I am having a solo exhibition at the university art museum at Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Quito, Ecuador. It’s furthering my on-going Flores para el Trueque project on floriculture workers. It will run September-November 2021 and will be viewable on the museum website.

I was also invited to curate a couple of online shows. I usually curate a show every few years, so simultaneously working on two curatorial projects has been a change of pace. Studio visits over Zoom are something new, and I think they worked fine. Last fall, I curated You, Me & They Portraying Us at Mount St. Mary’s University Los Angeles. The show included artists who create work that queries how one sees and represents oneself, perceiving other’s subjectivity, and results from the relationship between these two modes of reflection.

Common Ground: Artists Reimagining Community is currently at California Lutheran University, the second show I’ve worked on with Rachel. The curatorial theme questions how Covid-19 and the BLM socioeconomic, racial, and gender equity justice movement have influenced cultural workers’ definition and understanding of Globalism and the Global Art Movement. Inspired by mutual aid societies that assist community members in need and employing this as a curatorial strategy, I invited ten artists to exhibit who, in turn, each invited an artist who then each asked an artist to participate. The project continues to grow like a web.

0 Comments